Author

Leah Gibson

Catania Oils’ history goes back more than 100 years, but looking at the company’s high-tech manufacturing environment today, you’d never guess that the Basile family’s forebears once peddled oil door-to-door.

“If you ever watch CSI, that’s kind of how our lab looks,” says Stephen Basile, chief revenue officer and a member of the fourth generation. “We’ve just invested in nuclear magnetic resonance — NMR — which basically can test oil down to the molecular level. So, we take authenticity very seriously.”

The Ayer, Mass.-based company processes and packages plant-based oils, such as olive oil, peanut oil and vegetable oil. It sells to large food manufacturers like the makers of Stacy’s Pita Chips, Ken’s Salad Dressing and Cedar’s Hommus. It contracts with food service companies and sells to private-label brands. Annual revenue totals more than $500 million.

The company’s current success is thanks largely to the perseverance of previous generations of leaders, who kept the business going despite setbacks and tragedy.

The company was founded in 1900 by Giuseppe Basile, who sold oil in a small village in Sicily. In 1908, he and his wife sailed to America with about 10 to 20 barrels of oil. A bad storm struck the ship, and all of the barrels were destroyed. He arrived at Ellis Island with nothing.

Giuseppe eventually made his way to Boston’s North End, where many other Italian immigrants lived. He set up the business again, this time working out of a small, rented store with a couple of drums of oil. He would package the oil and take it from house to house in search of customers.

His son, Joseph, joined him in the work at a very young age. “He’d put gallons of olive oil in his burlap sacks and he’d go to school. And after the school bell rang, he would follow in his father’s footsteps and start selling oil house to house as well,” Stephen says. Joseph ended up leaving school and working for Giuseppe full time.

Joseph’s cousins were competitors in the oil business, and the two branches of the family argued over territory. The dispute was acrimonious and sometimes came to blows.

Giuseppe passed away in 1941, and Joseph took over at age 24. He instituted improvements, such as having lithographed cans made and bringing them to customers in a truck.

Joseph fought in World War II, as did one of his two brothers. The other brother stayed behind but had no interest in the business and sold off the equipment. When Joseph returned home, he found there was nothing left of the company.

Needing to start over, Joseph joined forces with his cousins. But they weren’t able to put their contentious history behind them, and the partnership lasted only a few years.

“My grandfather ended up buying out both of his cousins and other partners just because the relationship didn’t work out. And he persevered because it’s something that he really wanted — to continue to grow the legacy for the rest of his family members,” Stephen says.

It’s this era in the company’s history that explains how it got its name.

The company was called Basile Packing until 1946, when Joseph merged his business with his cousin Dominic Spagna’s business, Catania Importing. After bringing another cousin into the fold, the trio incorporated the company as Catania-Spagna.

While the partnership between the cousins was short-lived, that name remained until 2017, when the company rebranded as Catania Oils.

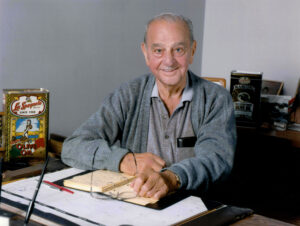

Anthony, Joseph’s son and Catania Oils’ CEO, remembers his father as a leader who was intensely dedicated to the company. “He worked very, very hard, and he worked seven days a week,” he says. “There were days that we didn’t see him at all because he would work — leave early in the morning, then come home around 5 o’clock. We’d have dinner, and then he’d go back to work until 10 o’clock at night and repeat that day in and day out. He was working all the time, but he was always fun to be with.”

At age 8, Anthony started going into work with his father and brothers on weekends, holidays, vacations and snow days. At first, he did simple tasks like cleaning bathrooms and emptying trash cans. As the years went by, he learned the more difficult parts of the operation, until at age 18 or 19 he could run every process. “We performed every job in the plant no matter what it was, jumping up on top of the tanks, loading trucks, two wheelers, everything was done by hand. There was no high-speed equipment like we have today,” he says.

Anthony continued his schooling and was recruited to play soccer at Bentley University in Waltham, Mass. But in 1974, a crucial employee left the company. Joseph, at age 55, was left to fill that employee’s physically demanding role of unloading rail cars. As Anthony was lacing up his cleats in preparation for a game, he couldn’t get the image of his father out of his mind. He quit school for good and went to work for Catania Oils full time.

“I regretted it at some point in my life, but today I don’t regret it. I would do it again,” he says.

Anthony’s older brother, Joe, had a serious illness, and his younger brother wasn’t old enough, so for a time Anthony took over the strenuous jobs like loading trucks, unloading rail cars and pumping and blending oil.

After they hired another employee to do that work, Anthony moved on to running the production, scheduling trucks and buying materials. In 1979, Joseph told him he’d always dreamed of one of his sons going into sales. “It’s going to be you,” he said.

Anthony agreed to work in sales. He went out on the road to sell oil and various other food items to restaurants. It was hard to get chefs to take him seriously, though, because although he was in his mid-20s, he still looked like a teenager.

At a restaurant in Waltham, a chef took one look at him and said, “I don’t need you, kid. Just leave.”

Anthony went out to the restaurant’s dumpster to check where it was sourcing goods. There, he found a Catania Oil case that must have been purchased through a distributor. Fed up, he turned around.

“I vowed never, ever to go into another restaurant to sell these grocery items that we sell. Went back to work, had a discussion with my father, my two brothers and another senior advisor that we had that we should eliminate all these grocery items, stop selling to restaurants directly and just sell oil to distributors or industrial users — someone that uses the oil as an ingredient for their product. And I didn’t get any resistance from my dad,” Anthony says.

In 1982, Joseph decided to divide the company’s stock equally between his five children. They had all been working in the business for years, and he knew he could rely on them to carry it on.

Joe became president of the company, and Anthony became vice president. They began expanding the business and modernizing the equipment, and they adopted some automated processes that were available at the time.

Joe’s health continued to deteriorate, and in 1988, he passed away at age 38. Now, 35-year-old Anthony was in charge of Catania Oils.

Anthony remembers his reaction to the new responsibility when he went into work the following day: “Holy crap.” Joe had handled the receivables, talked to the attorneys and accountants, and taken care of purchasing. Now, all of that was up to Anthony.

He had a hunch he would find his father at Joe’s desk, and there he was, holding the ship’s bell Joe had kept there. “What are we going to do now?” his father asked, distraught.

“He said, ‘Catania can’t see, can’t hear, can’t touch, can’t feel. You have to fight for her.’ And I promised him I would take care of it,” Anthony recalls.

Catania Oils continued to grow, and by the early 1990s, it was clear the company would have to move. The building was about 90 years old, with a tiny cellar, and the wooden boards on the second floor couldn’t bear any substantial weight. They had tried expanding into the building across the street, but that no longer provided enough space either.

They started the search for a new location and planned to construct a 50,000-square-foot facility.

“My dad said to me, ‘Put 100,000 square feet up. They’re going to need it.’ I said, ‘Dad, I can’t. I just can’t. I’m shaking right now by putting up this amount of money, because we’ve never spent that kind of money,’” Anthony says.

His father told him that in five years, he’d need an addition, but Anthony shrugged off the advice. That would be great, he said, but he couldn’t spend the money.

Sure enough, about five years later they had to add another 50,000 square feet. His father laughed at how precisely his prediction had come true. They were also hiring more employees, and they upgraded to high-speed equipment and bought many new tanks.

In 2004, they held an open house for family, friends and customers to view the new building. Anthony’s father was now 86 and in failing health, but they got him a golf cart he could use to drive himself around the plant.

At the event, Anthony found his father just sitting in one place, looking around. Anthony asked what he was thinking. “He said, ‘Not in my wildest dreams did I ever think I would live long enough to see something like this.’”

Anthony remembers that as the proudest moment of his career. “It’s not the amount of business that we’re doing; it’s that I made him happy,” he says. His father passed away soon afterward.

Anthony’s sons, Stephen and Joseph, who’s now the president, had been introduced to Catania Oils at a young age by their grandfather.

“My grandfather would pick me and my brother up every day on Saturdays, and he would take us into the plant,” Stephen says. “And we weren’t working on Saturday. The plant was down. He just enjoyed going to the plant every single day because it was his baby.”

When Stephen and Joseph were about 14, they got working papers and began to help out on weekends and over the summer.

“I’d be like, ‘What? All these people are going to Martha’s Vineyard and all these other places, and I’m stuck here because you’ve got this great deal on 5-liter cans of olive oils from Turkey, and you’ve gotten me a can opener instead of bringing in drums and totes in a more efficient way.’ But it was so cheap in cans. Me and my brother would sit there and open up containers and containers of 5-liter cans of olive oil to dump it in a bigger tub to then utilize it in our operation just because it sounded like the right thing to do at the time,” Stephen says.

Both brothers got some part-time experience working for outside companies as students, but on a very limited basis. Stephen started working full-time in sales at Catania Oils when he was still in college. Anthony made him promise that he would graduate, and he did; he also went on to get a master’s degree.

Joseph joined the company immediately after college. At first, he helped them bring in more computers and digitize the business. He also started working in sales. From there, he became a sales manager, and he worked to create a more formal organizational structure for the sales department. He then became more involved with operations.

“Early in my career, it was very closely held, and you wore 15 different hats because that’s the type of company that it was,” Joseph says. Now, in consultation with his father and brother, he added layers to the company’s hierarchy.

“We started to add these pieces based on necessity at the time. And it wasn’t until we were a little bit further down the road where it was like, ‘Okay, we’ve added a finance function. We’ve added more of an operations center person, HR,’” Joseph says.

Today, ownership is shared between 14 family members, and a board of directors oversees the company. The board comprises both family and non-family members. It includes the CEO, president, chief revenue office, chief financial officer, vice president of operations, vice president of human relations, vice president of engineering & maintenance and director of quality assurance. In addition to the board, the company has a team of advisors that includes CEOs and leaders of other specialty service companies.

Another change was the introduction of college internships. “I knew as my kids were getting older, there was no way that they would be 14, 15 years old working in this business,” Joseph says. His oldest son, now a sophomore in college, has done some part-time work in the company since he turned 18.

The family has made it clear to the fifth generation that they won’t be offered full-time jobs at the start of their careers.

“Just because your last name is Basile and you graduate college doesn’t mean that you need to come work here. And in fact, we don’t want you to come work here right away. Why don’t you go work somewhere else for three to five years, gain some outside experience and then bring some of that knowledge back here — if at that time you wanted to come back here. Maybe you found something else that you’ve really enjoyed and loved and want to continue to grow a career there,” Stephen says.

Looking back over the past few decades, operations at Catania Oils have undergone many improvements. Processes incorporate more technology, and they are now highly automated, less reliant on strenuous manual labor and far safer.

The company is focusing on vertical integration and is manufacturing its own PET bottles. “That has given us, I think, a little bit of a competitive edge, as well as more control of the supply chain,” Joseph says.

Looking to the future, he hopes to achieve a larger geographic footprint. Although they currently sell to every state, much of their distribution is still concentrated on the East Coast. He’d like to add manufacturing facilities throughout North America and continue to grow, while retaining Catania Oils’ distinct characteristics. Some hallmarks are holiday dinners for employees, charity events to honor their late uncle, and tank ceremonies to commemorate milestones.

“The tank ceremony of newborn family members is an olive oil blessing. So, they get christened with olive oil by my dad, right by their tank, and then the name goes on the tank,” Stephen says.

They don’t take their family ownership for granted. “Oftentimes, you’re competing against multinational, multibillion-dollar type of companies. And to some degree, that becomes a little bit of a competitive advantage because they can’t be as agile as us and as cost-competitive as us, but it also can be challenging. There are so many companies that were like us in our industry that have sold their businesses,” Joseph says.

As they plan for the next generations of the company, they recall one of Anthony’s father’s favorite sayings: “I don’t like cobwebs.” Anthony explains that the motto has always been a spur to keep innovating. “He wanted to see new equipment. He wanted to see new trucks. He wanted to see new customers.”

“You need to be able to embrace technology and automation and be willing to take those leaps of faith,” Joseph adds.

As originally seen on: familybusinessmagazine.com